André Holmqvist is Programme Manager at the London Festival of Architecture

Street scene, Hualien, Taiwan

A few months ago I travelled to Taiwan with the help of the British Council to meet with architects and architectural institutions. It has been the aim of the London Festival of Architecture to increase our international engagement, and with the help of the British Council’s Connections through Culture Grant I met some fascinating people and and discovered the architecture of a country which values historical preservation and community engagement in architecture.

To many Europeans, Taiwan is still the synonymous with ‘Made in Taiwan’. Although the bulk of manufacture gradually moved from Taiwan a few decades ago, the industrial heritage is still visible everywhere. The reuse and repurposing of the industrial heritage, and a layering of periods and styles in many ways became a recurring theme of my visit.

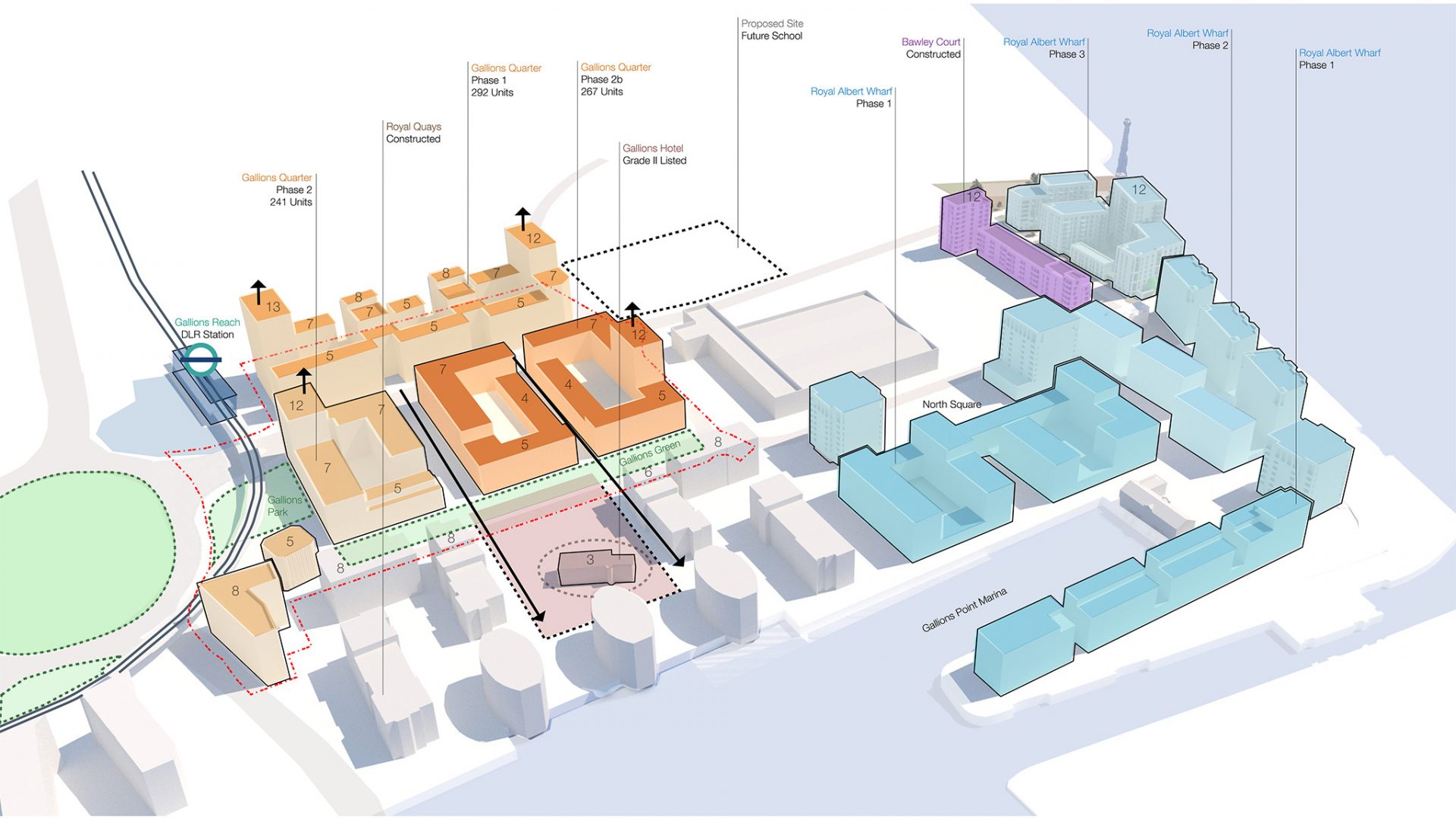

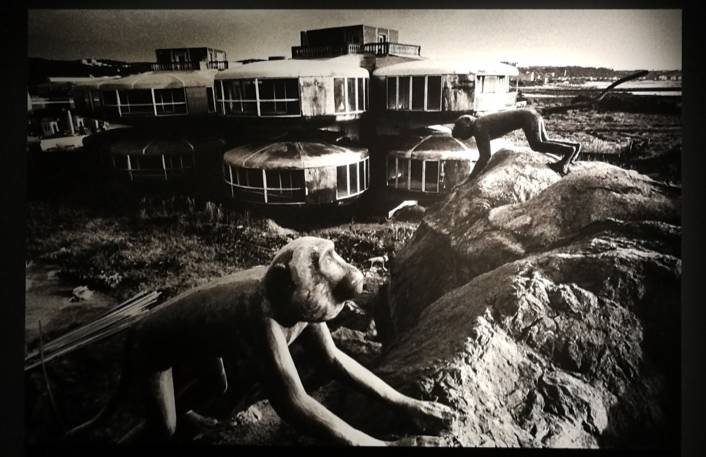

Recently opened, the Jut Museum in Taipei is the first museum in the country to focus on architecture and the future of cities. The director of the museum, Ms Huang Shanshan, showed me around their exhibition Paradise Lost which presented different aspects of urban transformation. One of the exhibited artists, Yao Jui Chung, explores the aftermath of Taiwan’s rapid urbanisation, with factories and real estate developments abandoned as the frenzied investment cooled off.

Yao Jui Chung, The Monkeys: Roaming around the Ruins IV, 1993

Many of the disused factories that still scatter the island nation’s cities have been preserved and repurposed, and a great number have been turned into museums and cultural centres. A prominent example in Taipei is the Huashan 1914 Cultural Park: a disused old winery turned into an artist village of galleries and performance spaces. The grey concrete architecture is softened by lush vegetation left to grow all over the old structures, and new walkways have been added to connect the buildings.

Huashan 1914 Creative Park, Taipei, 2005

A recent restoration project initiated by the Jut Foundation was the restoration and reconfiguration of a Japanese 1930s food market, now repurposed as the cultural centre Umkt (Xinfu Market). Architect Yu-Han Michael Lin divided up the open space with semi-transparent light-frame wooden walls that do not affect the original structure. While no longer functioning as a market, the Umkt project aimed to preserve the spirit of the Taiwanese market as a social meeting point. It is now is a cultural meeting space with cafés and facilities for food education. Located in a warren of small alleys in Wanhua, Taipei’s oldest district – with relatively aged population, the building was abandoned for a long time. It was a delight to find the space full of young people and arts students who make the covered market a destination and meeting point once again.

Umkt, Taipei, Yu-Han Michael Lin, 2017 ©umkt.jutfoundation.org.tw

Umkt, Taipei, Yu-Han Michael Lin, 2017

Anywhere you go in Taiwan, you are struck by the impressive investment in the cultural sector which can be seen in big cities and small towns alike, with newly created performance spaces, exhibition spaces and museums. For LFA 2019, Francine Houben, of Mecanoo architects, spoke about designing the newly constructed Kaohsiung National Center for the Arts – the world’s largest centre for the performing arts with four stages. I was shown around the centre by the head of international partnerships, Gwen Hsin-Yi Chang. When visiting, one is struck not only by the scale of the project, but also the openness of the architecture. Far from being an ivory tower of the high arts, the building invites the general public in from the surrounding park with a covered public plaza on the ground floor and an amphitheatre that cuts into the building’s façade.

Kaohsiung National Center for the Arts, Kaohsiung, Mecanoo, 2018

Creating architecture for people is also very much the aim of Fieldoffice Architects, led by Professor Huang Sheng-Yuan. Professor Huang received me at their practice, which is located in the middle of flooded rice fields outside the city of Yilan. As he told me, the vision of Fieldoffice is an eco-paradise of life in the countryside, which is apparent in their many projects which respond both to the surrounding countryside and existing architecture. By uncovering the underlying geography of the landscape they aim to heal the city piece-meal, bringing pockets of green to busy streetscapes and uncovering built-over rivers in the city centre. In the same vein, their Cherry Orchard Cemetery is a sculptural complex that emerges almost as a part of the mountainside. Instead of building a new pedestrian river crossing in Yilan, Fieldoffice created a ‘parasite bridge’ with a walkway suspended to the existing road bridge. Working with existing structures, the practice aims to add to the city’s historical layers and develop the collective memory of the place. The focus is always on people: when crossing the parasite bridge, you have to navigate around exercise bikes and built-in playground toys.

Cherry Orchard Cemetery, Yilan, Fieldoffice Architects, 2005-2014

Jin-Mei Pedestrian Bridge (Parasite Bridge) across Yilan River, Fieldoffice Architects, 2005-2008

Another stop on the tour was a meeting with the practice Atelier 3. The practice was founded by Taiwanese architect Hsieh Ying-Chun who devotes himself into what he calls ‘social architecture’. Hsieh has been helping people rebuild their homes since the 1999 earthquake in Taiwan. Atelier 3’s post-disaster reconstruction uses steel-frame structures that can be easily assembled with the help of residents from the homeless communities, ranging from a remote village in China and the disaster area of Southeast Asian Tsunami. The system can be adapted to include local building methods, ranging from wattle-and-daub to bamboo and stone wall panels.

Community reconstruction projects, Hsieh Ying-Chun ©architectureforpeople.org

A common sight in Taipei are rooftop extensions, often erected without permission. People add vegetable gardens or an extra room with self-built structures. For a 2011 exhibition entitled Illegal Architecture, Pritzker-prize winner Wang Shu and Hsieh Ying-Chun of Atelier 3 reflected on such spontaneous architecture with installations in Taipei. Wang constructed an eye-catching wooden structure on a Taipei rooftop and Hsieh created a suspended room straddling a narrow alleyway. The two installations explored how building technology can be made more easy so as to involve people in the construction of their homes without experts, resulting in an architecture responding more quickly to the needs of people.

Illegal Architecture, Taipei, Wang Shu, 2011 ©architizer.org; Illegal Architecture, Taipei, Hsieh Ying-Chun, 2011 ©taipeitimes.com

As I learnt from an exhibition at Huashan 1914 Creative Park, people in Taiwan have long had an active part in the construction of their own homes. In the 1960s, the Public Construction Bureau built a series of model houses that emphasised health and modernity. Floor plans were released to the public who were encouraged to take loans and build their own houses.

1960s plans and projections for model homes

Many thanks to the British Council for sponsoring this exchange through the Connections through Culture Grant and to the Taipei Representative Office for all their help; thank you also to Fieldwork Architects, Atelier 3, the Jut Foundation and Museum, Umkt (Xinfu) Cultural Market, Huashan 1914 Creative Park, and the Weiwuying Centre for the Arts.