Mattia Donato is a senior bioclimatic designer within AKT II. In this article, Mattia reflects on our theme of 'care', which for AKT II’s bioclimatic team means focusing on inclusivity, and on unlocking spaces for everyone.

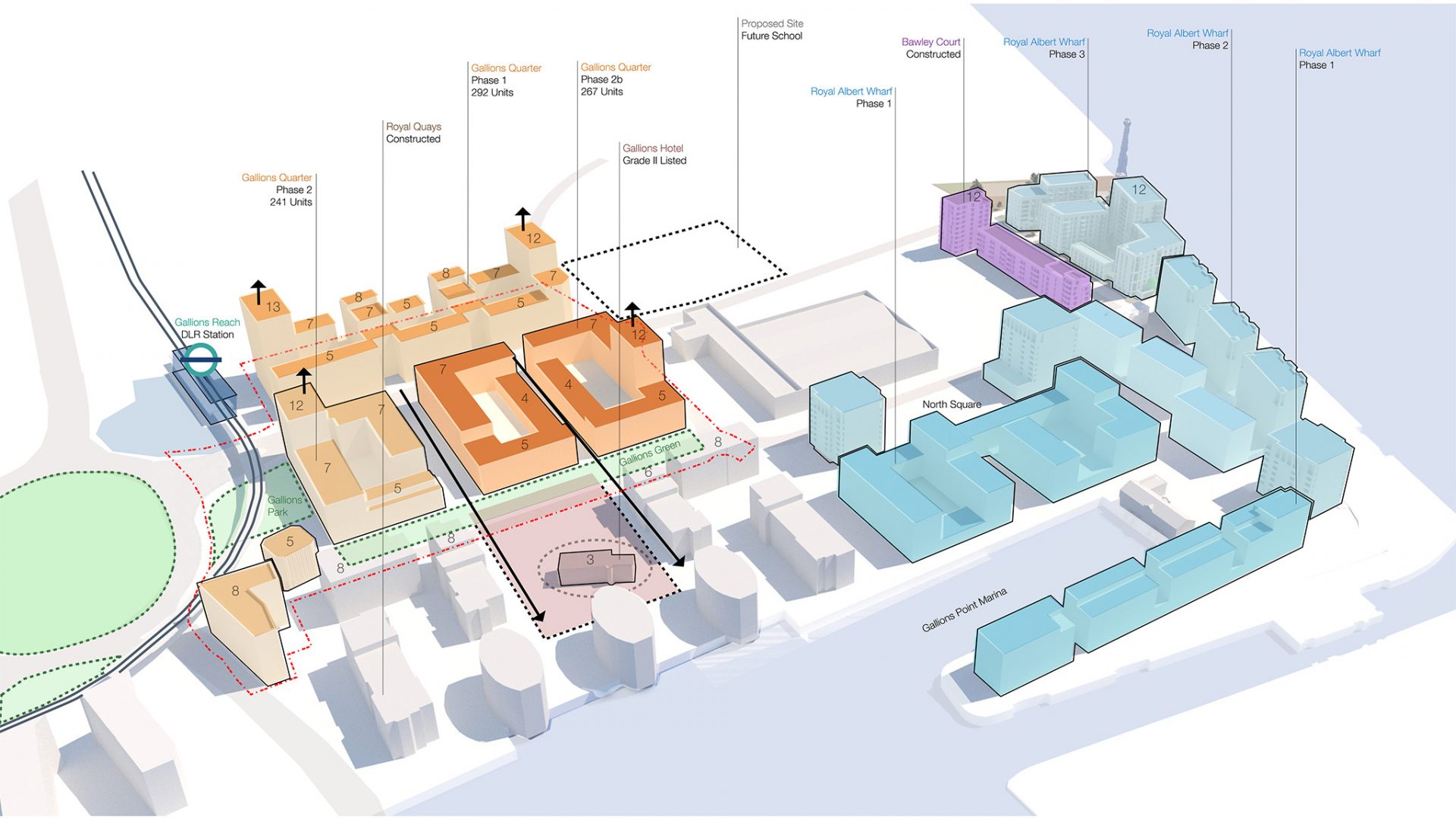

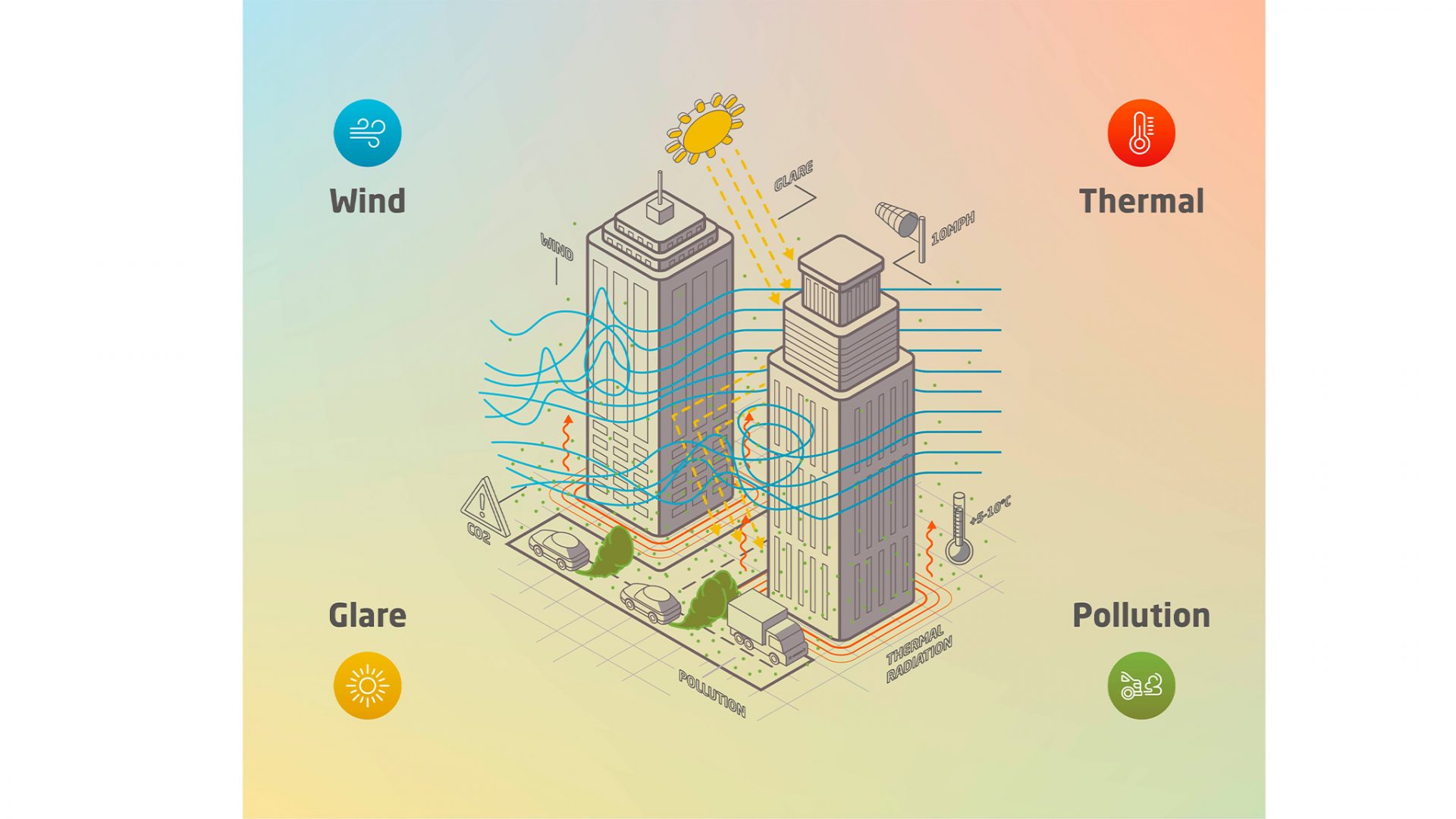

Image: Elements of Bioclimatic Design © AKT II

Bioclimatic design serves the intersection between ‘biology’ and climate’, and is essentially about designing buildings and landscapes with a response to the local climate so that people have a better experience. As bioclimatic designers, we also inherently care for the local flora and fauna, in the countryside and in densely built environments such as London, equally.

Clients, thanks to forward-thinking legislation from the City of London Corporation and from other UK local authorities, are today required to investigate the bioclimatic impact of their proposed developments. Relevant metrics will include wind effects, outdoor thermal comfort, local air quality, daylighting, and problematic glare.

For us, care means inclusivity, i.e. unlocking spaces for everyone from the very young pedestrians to the elderly, injured and frail. The Lawson Safety Criteria (as established within Tom Lawson’s 2001 publication ‘Building Aerodynamics’, and now widely adopted) quantify a necessary threshold of wind ‘slowness’ whereby a given space will then be suitable for everybody. This wind-speed threshold is defined as a maximum of 15 metres per second, and must be adhered to for all but 120 minutes of the entire (modelled) year.

On high-rise residential buildings, the issue of wind-induced vibration has recently become an essential consideration within the design stages, because it’s been identified as a risk to residents’ restful sleep! We apply aerodynamic analysis, to care for these occupants, accordingly.

The climate emergency, and its recognition by numerous firms, institutions, public bodies and local authorities, altogether requires us, as designers of the built environment, to think about the thermal experience of the people who use outdoor spaces when we’re designing any proximate building. These thermal conditions are typically assessed using the well-established Universal Thermal Comfort Index (UTCI), which accounts for wind conditions, operative temperature, solar radiation and humidity, holistically.

In December 2020, the City of London Corporation published some new ‘microclimate guidelines’, which specifically address outdoor thermal comfort. These have set a new industry standard, and are helping to quantify potential design decisions, in terms of recommended destination uses around the proposed developments.

Amidst our ever-changing climate, together with the concurrent race for space, it is the inhabitants of our densely packed, poorer neighbourhoods who will face the brunt of the urban heat-island effect. With the right tools, we can however tackle this urban heat-island phenomenon, as one effect of climate change, for everyone.

The ongoing transition to electric cars and heat pumps, while positive, is so far not keeping up with the comparatively fast growth of city populations; regardless of the Covid-19 emergency our cities will most likely eventually return to the centre of most people’s lives. Air quality is an invisible problem, and one that many of us have lived with since we were born, but this existing scenario of everyone breathing toxic air, from children to the elderly, doesn’t have to be our normality.

We are able to inform local authorities on the air-quality impacts posed by potential uses of buildings and land, and we can advise on measures that will accordingly increase what’s called ‘particle dispersion’. Where trees or other barriers are creating polluted pockets, we can indeed find alternative solutions. And we can encourage clients to adopt energy networks that avoid any local gas burning, which would otherwise compound the pollution problem.

Well-lit spaces are not just the result of well-designed buildings. They reveal well-planned urban districts. Access to sunlight is essential for everybody, old and young, and particularly for those who spend most of their time indoors (which lately has been many). There are however cases where new high-rise buildings threaten this right to sunlight, and it’s our duty to protect and care for anyone, or anything (e.g. a tree!), that could be affected. After all, developments can sometimes be more sustainable for some demographics, than for others.

Finally, we can prevent accidents throughout the urban realm by reducing any problematic glare for those who are driving vehicles of any sort – from bicycles and cars, to trains, and even aeroplanes. Indeed, a bioclimatic designer’s scope may routinely encompass modifying pedestrian-crossing, traffic-light and rail-signal locations, as well as setting maximum vehicle speeds for specific routes, and, perhaps more obviously, advising on the reflectivity of buildings’ envelopes.

For us, as designers, care is everything. And we’re optimistic that all local authorities and clients will fully embrace care, as part of moving ever further towards true, sustainable development.