- This essay by George Saumarez Smith, Director at Adam Architecture, was commissioned as part of a series of essays on identity and architecture for this year’s LFA.

Classicism runs deep in the veins of London. A long walk across the heart of the city would encounter classical buildings on every turn, from Somerset House and Greenwich Hospital to the Banqueting House and Covent Garden Market. All around us are classical buildings by great architects from across the ages: Hawksmoor, Gibbs, Chambers, Soane, Nash.

But Classicism lies too in more modest buildings, down to the simple houses arranged in streets and squares that make up so much of London’s urban fabric. These are not usually the works of great architects but of anonymous builders. In this British Classicism seems always to have excelled, so that a very plain house was given elegance simply by its repetition in a terrace, the proportions of its rooms and by the use of simple mouldings on its doors and windows.

I was born in Islington and vividly remember both its leafy squares and the urban grit of Upper Street in the 1970s before it was gentrified. At weekends we would drive out of London through the East End, fascinated by the melting pot of cultures along the Lea Bridge Road and out through the suburbs around Epping Forest in search of the countryside. If we were ever in London on a Sunday morning we would head down to the deserted streets of Smithfield, and then deeper into the City, searching for Wren’s churches around St Paul’s hidden like precious pearls. To this day if anyone asks me what buildings they should see on a visit to London, I invariably say the City Churches.

London has, of course, changed much in the last 40 years. Some parts have changed beyond all recognition, particularly those where clusters of tall buildings have appeared. All of this has altered London’s character immeasurably.

During this same time, serious new classical buildings have been few in number and modest in size. There were of course the jokey Post-Modern buildings of the 1980s accessorised with over-scaled classical details, which came to represent the vulgar excesses of Thatcherite Britain. But this style came to an abrupt end with the early 90s recession and whilst London boomed in the early 2000s, it seemed that Classicists had become stuck with only producing historical reproductions. What a difference this was from the invention of the 1920s and 30s that brought us Lutyens’ Cenotaph and Charles Holden’s underground stations.

Earlier this year I took part in a debate about the relevance of Classicism in the modern world. To me this seems beyond argument; classical architecture is all around us and part of who we are. But it seems that not everyone shares this view.

The debate took place in the crypt of a church in Clerkenwell. The audience were mostly young architects; this would surely make a refreshing change from the punch-ups between Classicists and Modernists that became such a tedious part of architectural debate in the 1980s.

I went up on stage to deliver an opening speech. Classicism, I argued, is an essential part of our cultural identity that has inspired artists and architects throughout the centuries. It ought to be properly studied and understood, and for too long it has been held in contempt by so-called ‘serious architects’. All of this holds us back, because a proper understanding of Classicism provides a foundation on which to understand construction, composition and proportion – what might be called ‘architectural good manners’. Too many new buildings seem to ignore these lessons and surely it would be of benefit to study them more closely in architecture schools. We live in an age of ever greater freedom of choice, acceptance and diversity, I said. It is time to re-evaluate the relevance of Classicism for a new generation, and to bring it back in from the cold.

On the other side of the debate was a Cambridge historian who was doing his PhD on inter-war British architecture. He quickly launched into attack mode and soon the insults were flying.

Architectural style, said this academic, was of little relevance when there were so many inequalities in modern society. What we should really be debating was political ideology, and modern Classicism, he said, was indelibly linked with ultra-conservatism. Designing classical buildings, therefore, put me alongside the pro-hunting lobby and religious groups opposed to homosexuality.

It also apparently made me responsible for a wide range of historical atrocities, from the slave trade to the Holocaust. The fact that I have designed a house in New Delhi linked me with extremes of injustice in Indian society, as well as for the worst aspects of British rule in various parts of the Empire over a hundred years ago. More recently, I could also be blamed for government failures over the Grenfell Tower tragedy and the lack of opportunities for black communities in deprived parts of London.

As these accusations were piled higher and higher, the atmosphere in the room became more and more boisterous. Each new insult was accompanied by yells of excitement from the audience, like an angry mob baying for blood. His parting shot was particularly stinging. ‘Why don’t all you Classicists go and live in Poundbury so we don’t have to look at you!’ The crowd roared their approval.

As I walked home on that cold February night, I wondered how this line of attack would have sounded if it had been directed at someone else. If, for instance, Classicists had been replaced with a religious or ethnic minority, being told to live somewhere out of sight. And how would that same audience have reacted?

I have thought a lot about this debate in recent weeks, and about the strange opprobrium still reserved by architects for new classical buildings. I have reached the conclusion that it is not about Classicism per se, but the fact that the buildings are new. There certainly doesn’t seem to be a problem if they are old. Architects love to travel to Venice, Paris or Rome and marvel at classical works, or even to live in old classical houses as many of them do, but the rules for new buildings are quite different.

This seems particularly odd as in recent years the margins of difference between classical and non-classical new buildings in London have become increasingly fine. A completely plain and flat building faced in brick or stone is allowed; this is the basis of the New London Vernacular. But as soon as you add a string course, some shallow pilasters and a cornice, you will invite the wrath of a whole profession.

Negative attitudes towards Classicism are forged in our universities through the way that architecture is taught. Classicism is seen purely as part of history, coming to an end with the advent of the Modern Movement in the early 20th century. When it comes to teaching design, students are rewarded for originality of thought, with innovation and difference promoted as ends in themselves. This necessarily rejects Classicism which is presented as irretrievably hide-bound by traditions and rules, despite the vast historical evidence of novelty and invention within the classical tradition.

On top of all of this is the political and ideological weight attached to Classicism, as I had found in the debate. The obstacles are made virtually insurmountable, with the result that after five years of study hardly any students pursue an interest in Classicism. Ironically the most frequent route for them is to become architectural historians; there could be no better way of keeping Classicism safely locked in the past.

Such attitudes have kept classical architecture on the margins for too long. In some ways this would not be a problem for society if better solutions had been found, but this is really not the case. Since the middle of the 20th century standards of design seem to have been getting progressively worse. Too many modern buildings in London are poorly designed and inflexible to changes of use. What kind of a legacy is this to be passing on to our children?

So what alternatives can classical architecture offer?

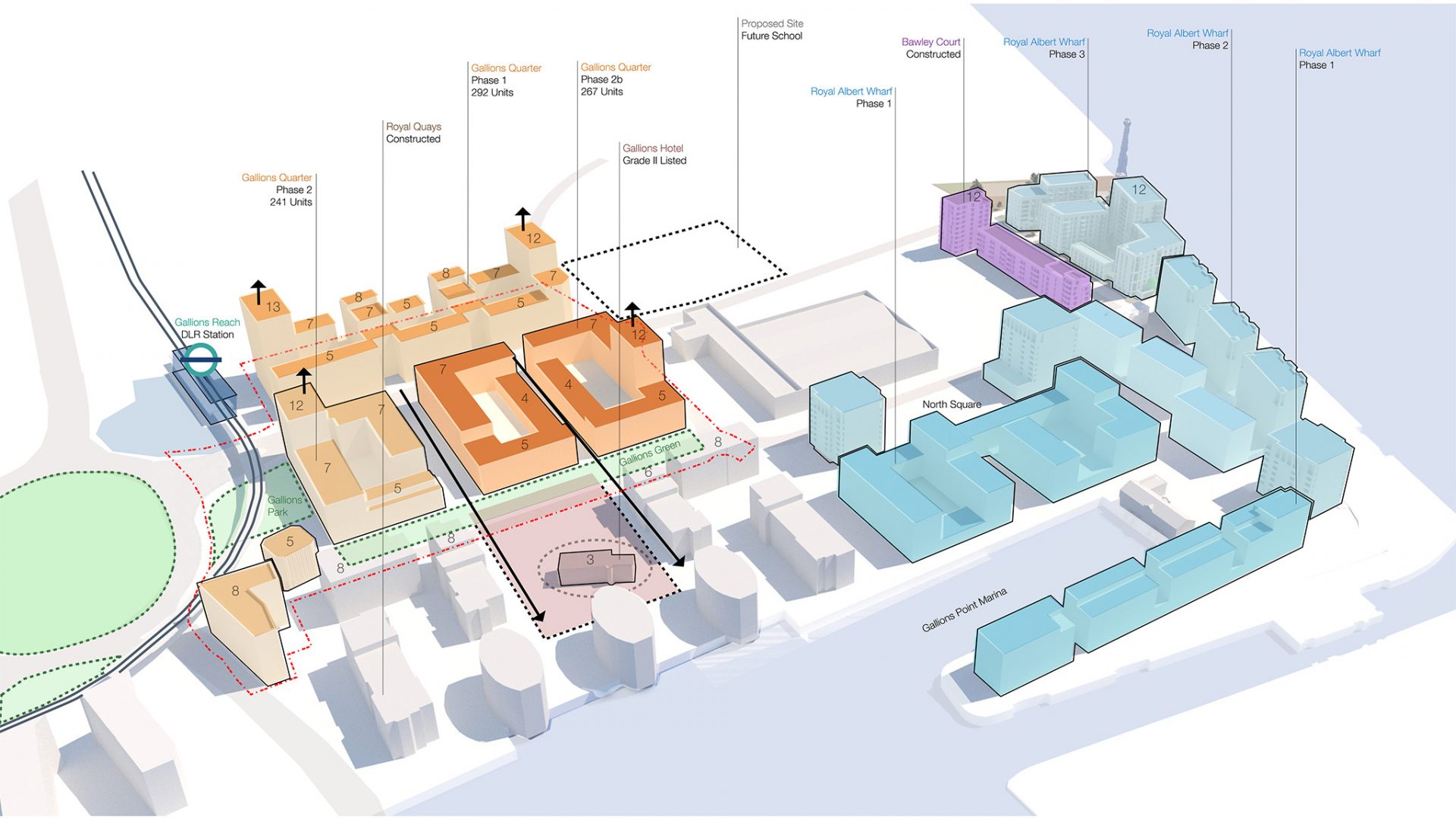

On a broad urban scale at a high-density, Classicism offers a better model than tall buildings through medium-rise development formed around streets and squares. This approach has recently been championed by the Create Streets movement and has been widely accepted across the profession since a similar conclusion was reached by the Urban Task Force in the late 1990s. But sadly these lessons seem to have been too often ignored, with high-rise tower blocks still appearing all over London. Just look at the City of London, whose skyline from the west now resembles a drunken crowd of photo-bombing pranksters parading behind St Paul’s.

At the scale of building groups, Classicism offers many lessons in distinctions between public and private space, adaptability, visual hierarchy and composition. These subjects were much discussed by polemicists of the early 20th century and explored in pioneering social housing projects of the period. I think particularly of the Peabody Trust in London or of the example set by other European cities such as Stockholm and Berlin, where social housing was designed with elegant simplicity whilst being clearly Classical in origin.

And at a finer scale, Classicism shows us how buildings should be decorated. This is where the infinite complexity of the classical language comes into play, based around the shapes and combinations of mouldings. They derive, ultimately, from the Five Orders which were for hundreds of years the basis of all western architecture. Shockingly, they are no longer taught.

Classicism is at the core of London’s identity, but it seems likely that a lack of appreciation of classical principles will continue to erode the character of the city. It would be good, however, to end on a positive note and there are signs amongst an emerging generation that the wheel is turning. For them, Classicism no longer carries political baggage but instead seems to offer a model of a more humane, attractive and natural architecture.

Over the centuries Classicism has been connected with everything from oppressive dictatorships to liberal democracy, why should it not now become a vehicle for a new more environmentally and socially conscious generation? The future is still up for grabs, why should it not be classical?

– George Saumarez Smith